Table of Contents

What is public key authentication?

This article was written by Kevin Kimani, a passionate developer and technical writer who enjoys explaining complicated concepts in a simple way. You can check out his GitHub or X account to connect and see more of his work!

Public key authentication is a foundational security mechanism used across modern systems, from HTTPS and SSH to passkeys and API authentication. While many developers interact with it indirectly every day, the underlying model is often obscured by tooling and abstractions.

Public key authentication is a cryptographic system that verifies an identity and secures their connections without ever sending passwords or secrets over the internet. It uses pairs of mathematically linked keys, one public and one private, to create cryptographic proof that the user is who they claim to be, all while keeping the actual credentials safely locked on their device.

In this guide, you'll learn how public key authentication works and how it underpins many of the security guarantees modern systems depend on.

What is public key authentication?

Public key authentication is an authentication model based on proof of possession rather than shared secrets.

Instead of verifying identity by checking whether a client knows a password, the verifier challenges the client to prove that it possesses a specific private cryptographic key. That proof is generated using asymmetric cryptography and can be verified with the corresponding public key.

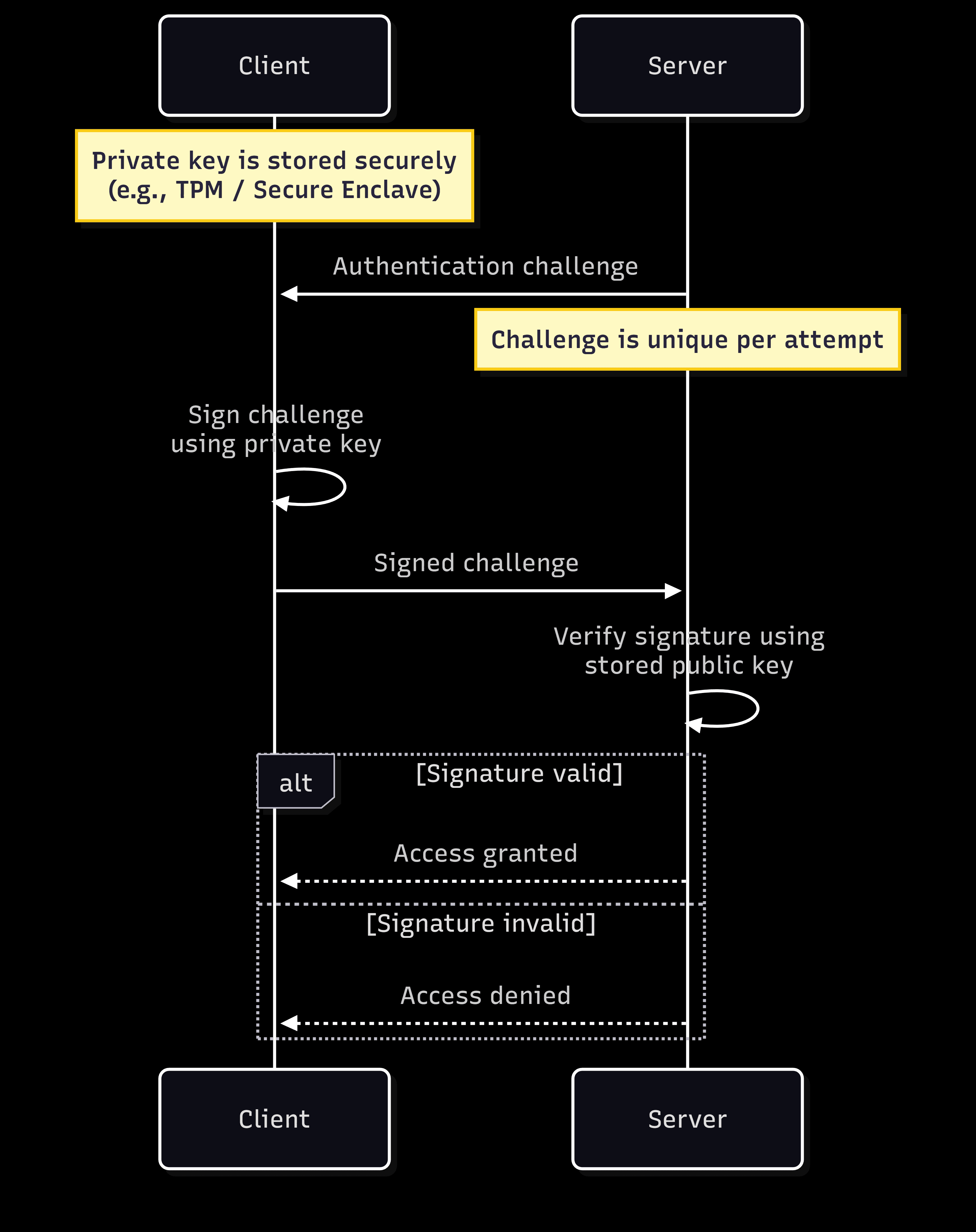

At a high level:

A system associates an identity with a public key.

During authentication, the verifier sends a unique challenge.

The claimant signs the challenge using the private key.

The verifier checks the signature using the stored public key.

If the signature is valid, the system has cryptographic proof that the claimant controls the private key associated with that identity. No shared secret is transmitted, stored, or compared during this process.

Security advantages of public key authentication

The most immediate advantage of public key authentication is that it eliminates entire categories of password-related vulnerabilities. No passwords means no forgotten credentials, no reuse across accounts, no exposure in data breaches, and no risk of phishing attacks. Attackers also can't credential-stuff their way into accounts or brute-force weak passwords because there are no passwords to attack.

Public key systems also provide strong, mathematically verifiable identity verification. When a signature is validated using a public key, you have cryptographic certainty that the holder of the corresponding private key created it. The cryptographic operations either succeed or fail. There is no ambiguity.

Public key authentication also enables non-repudiation, meaning you can cryptographically prove who signed or created something. If you sign a document with your private key, you can't later deny having done so because only you possess that key. This is valuable for legal documents and code signing, where accountability is essential.

Core concepts behind public key authentication

To really understand why public key authentication works so well, let's look at the concepts that make it possible.

The foundation: asymmetric cryptography

Asymmetric cryptography is the foundation of public key authentication. It's a cryptographic system built around two keys that are mathematically linked but behave very differently.

One key is a public key and can be shared freely with anyone.

The other key is private and must stay hidden. It never leaves the device that created it.

These two keys work together in a special way: Data signed with the private key can be verified with the public key, and data encrypted with the public key can be decrypted with the private key. This relationship makes it possible to prove identity, secure communication channels, and create digital signatures without ever relying on shared secrets or traditional passwords. It's the foundation behind modern authentication flows, encrypted browsing, secure APIs, and almost every trusted interaction that happens on the internet today.

Digital signatures

A digital signature is a cryptographic proof that a message or document came from a specific person or system and hasn't been tampered with. The process works by using the user’s private key to create a signature for a piece of data. Anyone with the matching public key can verify the signature and confirm that the holder of the private key signed the message and that the data has not been modified since it was signed.

Key exchange

While asymmetric cryptography is powerful, it's computationally expensive compared to symmetric encryption, where both parties use the same secret key. This creates an interesting challenge: symmetric encryption is fast but requires both parties to share a secret in advance. Asymmetric encryption can establish trust without pre-shared secrets, but it's slower for encrypting large amounts of data.

Key exchange protocols, like Diffie-Hellman and its modern variants, solve this by using asymmetric cryptography to securely establish a shared secret between two parties, even over an insecure network. Once both sides have the shared secret, they can switch to faster symmetric encryption for the actual data transfer. This is exactly what happens when the user connects to an HTTPS website. The browser and the server use asymmetric cryptography during the TLS handshake to agree on a symmetric key, then use that symmetric key to encrypt all the actual web traffic.

Certificate authorities

There is a trust problem in public key cryptography; you need to verify that a public key actually belongs to whom it claims to belong to. An attacker can potentially trick you into accepting their public key while claiming to be your bank, allowing them to intercept your communication. Certificate Authorities (CAs) solve this problem by issuing digital certificates that bind public keys to identities like domain names.

When a website wants an HTTPS certificate, it generates a key pair and sends a certificate signing request to a CA, along with proof that it controls the domain. The CA verifies this proof and issues a signed certificate. Your browser comes preloaded with a list of trusted CAs, so when you visit a website, your browser can verify the certificate chain. This system of trust, called public key infrastructure, is what makes the padlock icon in your browser meaningful.

How public key authentication works: step-by-step

Let's walk through how public key authentication works. This demonstration uses passkeys as the example since they're a modern implementation of public key authentication. But public key authentication also exists beyond passkeys.

The setup

Before a user can authenticate with a passkey, there's a one-time setup process. When the user creates a passkey for a service like Google, GitHub, or their bank, their device generates a new key pair specifically for that site. The private key is immediately stored in their device's secure enclave or Trusted Platform Module, which is a dedicated hardware component designed to protect cryptographic keys. The matching public key is sent to the service they’re setting up authentication for and stored in their database alongside the account information. The service does not need to protect this key with the same level of security since it's public by design. However, its integrity must still be protected within the service's database to ensure it's correctly associated with the user’s account and hasn't been tampered with.

The authentication process

When the user tries to sign in, the server generates a challenge, which is essentially a random string of data that's unique to this specific login attempt, and it's sent to the user’s device. The device receives the challenge and prompts the user to verify their identity using Face ID, fingerprint, or PIN. Once they complete this step, the device uses the private key stored in its secure enclave to sign the challenge. This signature is then sent back to the server, which uses the public key stored during setup to verify that the signature is valid and was indeed created by the matching private key. If the verification succeeds, they’re authenticated and granted access.

The security difference

What makes this approach different from password-based authentication is that the private key never leaves your device at any point during the authentication process. No secrets are transmitted over the network where they could be intercepted by attackers. Instead, authentication relies solely on cryptographic proof of possession; the user’s device proves it has the private key by signing the challenge. Authentication relies solely on cryptographic proof of possession. No reusable secrets are transmitted or stored server-side, eliminating phishing, credential reuse, and credential stuffing attacks.

The security model shifts from "what you know" (a password) to "what you have" (a device with the private key) with "who you are" (your biometrics or PIN). This eliminates entire categories of attacks like password reuse since each passkey is unique to its service, phishing, and credential stuffing. Thanks to the FIDO2 and WebAuthn standards, passkeys also work across devices and platforms, making secure authentication feel effortless.

Where else can public key authentication be used?

While passkeys are a great example of public key authentication, the same underlying technology secures other countless systems, including HTTPS and JWT signatures.

HTTPS/TLS

HTTPS and TLS are great examples of public key authentication. When the user connects to a secure website, the browser verifies the server's certificate against trusted CAs to confirm they’re talking to the legitimate website. The server proves it possesses the corresponding private key through cryptographic operations during the TLS handshake. Once authenticated, both sides use key exchange to establish a symmetric key for encrypting all the data flowing between the browser and the server, keeping it safe from eavesdroppers.

JWT signatures for API authentication

JSON Web Tokens (JWTs) are widely used for API authentication, and when they use asymmetric algorithms, their signatures become tamper-proof. In this model, the authorization server signs the JWT using its private key, embedding claims about the user's identity and permissions. Any service that receives the token can verify the signature using the server's public key without contacting it for every request.

JWTs are ideal for distributed systems where you want stateless authentication.

JWT signatures ensure that tokens have not been tampered with and came from a correct issuer. Here's how to verify a JWT signed with an RSA public key using Python and the PyJWT library:

py

import jwt

def verify_jwt(token, public_key_pem):

try:

# Verify and decode the token

payload = jwt.decode(

token,

public_key_pem,

algorithms=['RS256'],

issuer='<YOUR-AUTH-SERVER>',

audience='<YOUR-API>'

)

print(f"Token verified! User: {payload['sub']}")

return payload

except jwt.InvalidTokenError as e:

print(f"JWT verification failed: {str(e)}")

return None

# Example usage

token = "eyJhbGciOiJSUzI1NiIsInR5cCI6IkpXVCJ9..."

public_key = """-----BEGIN PUBLIC KEY-----

MIIBIjANBgkqhkiG9w0BAQEFAAOCAQ8AMIIBCgKCAQEA...

-----END PUBLIC KEY-----"""

verify_jwt(token, public_key)In this example, the verification process checks the signature using the public key, ensuring the token was signed by the holder of the corresponding private key and hasn't been modified. If the verification succeeds, you can trust the claims inside the token.

SSH for server access

Developers and system admins use SSH (Secure Shell) to access remote servers securely, with public key authentication as the preferred method. You generate an SSH key pair on your local machine and add your public key to the server's authorized_keys file. When you connect, the server requests proof of possession of the private key. Your SSH client then generates a cryptographic response by signing specific session data (which includes a server-generated challenge) with your private key, proving you possess the authorized key without transmitting it. This enables automated deployments and infrastructure management without hardcoded credentials.

Setting up SSH key authentication is significantly more secure than password-based login. To start, generate a key pair on your local machine using the ssh-keygen command:

ssh-keygen -t ed25519 -C "custom_identification_text" -f ~/.ssh/my-example-ssh-keyThe -t flag selects the key type, -C adds a comment to help identify the key, and -f specifies the output file name.

This command creates two files:

~/.ssh/my-example-ssh-key: The private key, which should be kept secret~/.ssh/my-example-ssh-key.pub: The public key

Next, copy your public key to the remote server's authorized_keys file using the ssh-copy-id utility:

ssh-copy-id -i ~/.ssh/my-example-ssh-key.pub USER@SERVER-IPOnce configured, you can connect to the server without entering a password. The SSH client automatically uses your private key to prove your identity:

ssh -i ~/.ssh/my-example-ssh-key USER@SERVER-IPFor added security, you can disable password authentication entirely on the server by editing /etc/ssh/sshd_config and setting PasswordAuthentication no.

Code signing

Code signing verifies that software comes from a trusted source and has not been tampered with. Developers sign their apps, browser extensions, and container images using their private key. Operating systems, app stores, and browsers verify these signatures before allowing the code to run. When you download an app or install a Chrome extension, you're trusting verification of the developer's signature. This chain of trust protects you from malware.

Email encryption

Email encryption protocols like Pretty Good Privacy (PGP) and Secure/Multipurpose Internet Mail Extensions (S/MIME) use public key cryptography to secure communications. You share your public key openly, allowing anyone to send you encrypted emails that only your private key can decrypt. You can also sign emails with your private key so recipients can verify the message really came from you.

While these technologies haven't achieved mainstream adoption like HTTPS or SSH, they are helpful for journalists and organizations handling sensitive communications.

System | What’s Being Authenticated | Who Holds the Private Key | Verification Method | Common Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Passkeys | User > Service | User’s device | Signed challenge-response | Passwordless login |

TLS / HTTPS | Server > Client | Server | Certificate + TLS handshake | Secure web traffic |

JWT (RSA/ECDSA) | Token issuer > API | Authorization server | Signature verification | Stateless API authentication |

SSH | User > Server | User’s machine | Signed session challenge | Secure server access |

Code signing | Publisher > OS / Runtime | Developer or organization | Signature validation | Malware prevention |

Email (PGP / S/MIME) | Sender > Recipient | Email sender | Message signature verification | Secure and authenticated email |

Considerations for public key authentication

One of the most important considerations for public key authentication is key management. If a user loses their private key, they lose access, and depending on the system, recovery may be difficult or impossible. Many modern systems handle this through secure cloud syncing, but for SSH keys, you're responsible for backup and recovery planning.

Key revocation can also be challenging, particularly with certificates. If a private key is compromised, you need a way to tell the world that the corresponding public key should no longer be trusted. CAs use Certificate Revocation Lists and protocols like Online Certificate Status Protocol to handle this. For other systems like SSH or passkeys, revocation means removing the public key from the authorized list.

Implementation hygiene is another consideration when working with cryptography. Always use well-tested, vetted cryptographic libraries like OpenSSL or platform-provided APIs rather than implementing cryptographic operations yourself. Custom implementations are notoriously difficult to secure and are often vulnerable to timing attacks and side-channel vulnerabilities.

Conclusion

Public key authentication is the cryptographic foundation that powers much of modern internet security.

As you implement security systems in your own projects, use the information here to make informed decisions about when and how to use public key authentication. Remember to prioritize key management, plan for revocation in case a key is compromised, and always rely on vetted cryptographic libraries rather than rolling your own implementation.

For more breakdowns of authentication concepts, subscribe to the Descope blog or follow us on LinkedIn, X, and Bluesky.